The Use Value of the Past

Petermichael von Bawey

I was asked to contribute a small article to this student journal. I am happy to do so, especially since it offers me the opportunity to discuss certain topics of the course "Contemporary Germany" that I teach every other semester.

At first sight, the course might fall within the normal genre of "national history" and as such exam the usual chronology of historical events. Yet in teaching "Contemporary Germany" several more weighty factors related to German history come into play. The course, for example, begins with the year 1945, the end of World War II. Consider the date for a moment. For many historians, the year 1945 stands at the center or the end of their narratives of German history. Take the work of Hans Kohn, The German Mind, a classic text for decades and popular when I was a graduate student. Kohn begins his study with the Middle Ages and argues that all German history from 500 years ago led to the Nazi years, the culmination and end of German culture. The book does not stand alone. Peter Viereck’s The Roots of the Nazi Mind has a similar chain of being evaluating important historical events with progress toward National Socialism. Other historians who do not follow such a strict causal and linear--we call it diachronic--argument still find difficulties in explaining the Nazi years. The eminent German historian, Friedrich Meinecke, so overwhelmed by the Nazi era wrote in his The German Catastrophe that Germany took a wrong turn in history and suggested the creation of “Goethe Institutes” that would again teach the humanism of one of Germany’s great poets. Indeed, the question is still asked: How did a nation of philosophers and musicians become one of criminals and barbarians? In an effort to consider the problematic of German history, the German government has taken up Meinecke’s suggestion and established “Goethe Institutes” worldwide for the study of German language and history.

Nevertheless, explaining how Hitler came to power or how the Nazi dictatorship could take a hold of German society and culture, and how the 3rd Reich could reach such levels of destruction and barbarism have been the focus of many historical examinations of German history. In addition, examinations of the Nazi era itself are frequently related to a broader study of German history. For example, historians tend to view 1933 with Hitler’s seizure of power and the end of democracy in Germany through the politics of the 1848 revolutions, when Germans failed to establish a democratic state. Others view Hitler’s annexation of Austria (1938) and the Sudetenland with the destruction of Czechoslovakia (1939) in light of Bismarck’s politics of 1866 to 1871 with the creation of the 2nd German Empire. The date 1918 with the end of the 2nd Empire is often compared to 1945 with the fall of the 3rd Reich.

There are several reasons why historians of Germany place 1945 in the center or at the end of their historical narratives. For one, the 3rd Reich may have lasted a mere twelve years--a brief span in history’s life--yet in that short period Germany had a more profound effect on the rest of the world than in previous centuries. Moreover, the moral and historical abnormalities of Nazism and its crimes have led historians to examine “abnormalities” in the longer span of German history. Was Martin Luther’s “authoritarian personality”and his appeal to state authority against the peasants after 1521, for example, an early “appeal to state authority” that later made Nazism possible? Was Bismarck’s “blood and iron” policy another precursor that reappeared after 1933? Historical examples abound and it is apparent that the burden of the past weights heavily on recent German history.

There is another consequence of 1945 and that is the division of Germany into a West Germany (May 1949) and East Germany (October 1949), one capitalist and democratic, the other communist and authoritarian. With that division there was an end of a German history that had Prussia as its center.

Prussia emerged as a strong German state after 1740 with King Frederick II’s successful attack on the Habsburg Empire. With military skill, discipline and luck--the death of his enemy Tsarina Elisabeth--Frederick had forged Prussia into a powerful European state when the wars ended in 1763. Emerging victorious with the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, Prussia developed into a modern industrial state, which by 1866 successfully challenged the Habsburg Empire for German supremacy. In 1870 Prussia defeated Napoleon III and its chancellor Bismarck united the German states under Prussian dominance to create the 2nd Empire. That Empire was Prussian in government and social organization and established the provincial Prussian town of Berlin as Germany’s national capital. The Empire’s defeat saw a truncated Prussia with the reappearance of Poland in 1918. When Stalin drew the Oder/Neisse border between Germany and Poland there was little if anything left of Prussia, which was declared officially dead in 1947. The German state, Prussia, that had created modern Germany had disappeared in 1947 and with it vanished a part of German history, one that had shaped it for at least 250 years.

The Germans call 1945 the “Stunde Null,” the zero hour. Rossellini, the Italian director, made a fine film bearing the title, depicting social conditions in Berlin at that time. One could say that 1945 is the zero hour for another reason: 1945 was the time when German history began again after a good part of it was wiped out by the Nazis and then by the Allies. From 1945 to 1949 there was no German state and when the two German states were created in 1949 they were of Allied production, and so were German politics east and west for the subsequent years of the Cold War. It was not until Chancellor Willy Brandt’s “Ostpolitik” also called the “politics of the small steps” that West Germany ventured briefly into a quasi-independent foreign policy in 1969. But by then the political lines of the Cold War had harden, the Berlin Wall in place since 1961, and the idea of one German nation only a memory.

Historians in East and West Germany were writing histories of not one but of several Germanys. East German historians claimed Frederick II and Martin Luther in part to legitimize East Germany itself, not recognized by the Western Allies until 1972, whereas West German historians focussed on regional identity--Baveria, the Rhineland--that challenged a national one. That regional identity questioned as well Bismarck’s creation of the 2nd Empire in 1871, one viewed now as artificial and lasting only a few decades (until 1918). Besides, the Treaty of Versailles ending W.W.I and Hitler’s annexation of Austria and the Sudetenland had transformed Bismarck’s concept of the German nation, based on the “small German solution” and not the “large German state” including the Habsburg lands (Austria and Bohemia).

Since the French revolution (1789), France has undergone many experiments in government from return to monarchy during the restoration to the building of two Napoleonic empires, from occupation and division to the creation of five republics. Yet through all of these radical political upheavals France retained its basic unit, the nation-state. Not so Germany, where national fissures were more radical and lasting. Bismarck’s experiment of 1871, the creation of a German nation-state, was viewed as partial, flawed and a temporary condition that was in any case unmade by Hitler. France can to this day continue its myths of progress and improvement, despite its radical transformations, yet for Germany the idea of history as a steady progression toward freedom--central in the German philosopher Hegel’s notion of history--was askew and out of place, at least since 1933 and certainly since 1945. Consider Borovsky’s television chronicle of Western Civilization that began in the mud of the Mesopotamian river valley and ended in the mud of Auschwitz, or consider the question of the German philosopher Theodore Adorno, who asked was poetry possible after Auschwitz? The break in German history seemed complete.

In response to this divided and fragmented Germany a new approach to history emerged with the works of neo-conservative historians like Ernst Nolte, Andreas Hillgruber, and Michael Stuermer. Their writings provoked the "historian's debate" in 1986 that unleashed a tempest in the academic world with heated discussions worldwide that have now subsided but have not ended.

In summer 1986 Ernst Nolte proposed a new approach to German history. Already internationally known for his study Fascism In Its Epoch , where he linked the French, Italian and German fascist movements, Nolte now argued that the crimes of Nazism were not unique to world history as many historians had stated. Rather Nazi crimes were similar in degree, kind and even scale to other crimes of the 20th century including Stalin’s extermination of the kulaks (estimated 20 million dead) and Pol Pot’s auto-genocide against the people of Cambodia.

Nolte took his argument further with suggesting that Stalin’s Gulags were a model for Hitler’s death camps. For Nolte Nazism itself was a response to Soviet communism with the mass murders of the Bolsheviks a threat to the rest of Europe eliciting Nazi retaliation. By comparing events of Nazi Germany to those of the Soviet Union, Nolte had linked German history of that period to a wider European one and established a synchronic narrative on the level of macro-history. That is, he coupled the evil of the Nazis to that of the Bolsheviks and by analogy found similarity. Thus Nolte historicized the 3rd Reich and gave to German history a broader continuity, one that started before Nazism and continued to current events. In addition, his historical comparison had "unburdened" German history of the Nazi era weight of evil.

The liberal Hans-Ulrich Wehler labeled Nolte's work a "borderless misdeed of erroneous comparison" and Peter Gay accused Nolte of "trivializing" the Holocaust. The Hitler expert Eberhard Jaeckel pointed out that Hitler's anti-Semitism was public knowledge with the publication of his Mein Kampf in the 1920s. Therefore, Hitler's war against the Jews was a consequence of his early ideas shaped in Vienna before W.W.I and not a response to Bolshevik terror in Russia after 1917.

Objectionable too was the scale of Nolte's comparison. Wehler doubted that it was possible to compare Pol Pot's "stone age communism" with its brutal extermination of Cambodians to Hitler's efficient and highly industrialized murder machinery. The comparison with the Soviet Union was questioned as well. In the past two decades, studies of totalitarian governments have drawn many parallels between the brutal governments of Hitler and Stalin. Yet other historians have argued for another reading of history. Germany was historically a part of the great Western tradition of the advancement of science and technology, and of the values of Christianity, Humanism and the Enlightenment. Russia, on the other hand, had missed the Renaissance and the Enlightenment and that had left an impact on its culture, one that the historian Theodore von Laue and the political theorist George Kennan argued retained an "authoritarian political culture." In fact, what had shocked historians like Friedrich Meinecke was that Hitler's terror and destruction could happen in Germany with its great cultural heritage, one unable to prevent Nazism from taking over the country. Leonard Krieger in The German Idea of Freedom drew the conclusion that more emphasis was given to culture than politics in Germany. Thus not only is Nolte's comparison faulty, but the added weight of Germany's cultural history tilts the scale of comparison.

The historian's debates were from beginning to end about the "politics of memory" in an intellectual struggle over German history, the German nation, divided at the time, and the burden of the German past. Although not stated by the academic combatants, the historian debates were also about the "use value of history." Just as the playwright Bertolt Brecht "plundered" earlier dramas for their "use value" (Gebrauchswert) in writing his own works, so the historians "took history" to write "history."

Take Michael Stuermer's statement that "As Dresden in a February evening burnt--more than 70,000 deaths were counted--this was a German Hiroshima!" The comparison of the British fire bombing of Dresden to the US dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima should call for similar unease according to Stuermer. Yet Hiroshima's destruction is written far larger in human memory than Dresden's fate.

What too had faded from memory with the disappearance of Prussia is that Germany was historically the land of Europe's center. Turning to geopolitics, Stuermer finds that in Germany's older geography there was a "curse" that condemned the nation to power politics of the land in the middle. Germany's "destiny" was coupled to "temptation and damnation," burdened by its geography in Europe's center. Thus the place of "German history, in the center of Europe, signifies still and will for the future her first condition." In short, all else--the two world wars, the horrors of the Nazis, the division of Germany--follows that “first condition” of geographical determinism. The implication of Stuermer's "history" is clear: Nature is the cause of German politics, and there is nothing we can do about it! Here a deus ex machina--an external, non-human force-- has "unburdened" the German past.

The historian Andreas Hillgruber's studies of the German past led to his examination of several "identification options." In his evaluation, he could certainly not "identify" with Hitler and his Germany. However, he could also not identify with the "victors"as long as the Allied armies held Germans prisoners, for he "shared the fate of the German nation in its totality."

Hillgruber finds it not possible either to identity with the "men of 20 July 1944" who attempted to assassinate Hitler and create a new German government. Not challenging their "ethics," Hillgruber does question the "time" of their engagement when they knew that the Red Army was on the way to East Prussia (the home of many Prussian aristocrats who participated in the coupe against Hitler). With this choice too there is a problem. For instance, I know that Countess von Moltke, whose husband Helmut James was murdered by the Nazis for his participation in the resistance to Hitler, would object with Hillgruber's reservation. When an undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Cruz, I spoke with Countess von Moltke and she informed me that her husband wanted a democratic Germany and that he had engaged himself for that political idea. Many books on the event discuss the political ideals of the “men of 20 July 1944” and a memorial site with archive documents their resistance to Hitler.

Finally, Hillgruber can identify himself with the "concrete fate of the German population in the East and with the desperate and selfless efforts of German Army East." Again, Hillgruber's choice is open to another reading of the German past. Certainly as a German of the East who with his family fled the approaching Red Army in late January 1945, I should have personal cause to sympathize with Hillgruber's choice. We like millions of East Germans fled in fear of the Red Army's terrible retribution for Hitler's brutal war in the East; and millions of East Germans perished in the westward trek of that harsh winter, including my sister. Yet I also know that as we fled our home town, Kattowitz (today Kattowice), the Red Army liberated the concentration camp inmates of Auschwitz thirty kilometers to the southeast. The "selfless efforts of the German Army" may have given us additional time to prepare our flight--what my grandfather would dispute as German soldiers confiscated his car, but the resistance of the German army certainly delayed the liberation of the concentration camp victims.

Hillgruber's schema of identification models is either too broad or too narrow to allow for the sharing "of the fate of the German nation in its totality." Furthermore, the phrase of "the German nation in its totality" is a questionable, abstract notion. When was the German nation "in its totality?" Was it before 1933 with the Germany of the borders drawn by the Treaty of Versailles? That would exclude many Germans. Was it the Germany after 1933? That too would exclude many Germans. It certainly could not have been the divided Germany after 1945. Could Hillgruber refer to the 2nd German Empire of 1871 as "the German nation in its totality?" But that too is questionable as that "German nation" included the Alsace and Lorraine. The many disjunctions of German history void the phrase of historical meaning.

As the historian's debate intensified and spread to the United States, historians like Saul Friedlander called for a "new style" with focus on more “historical description,” that would offer “documentary precision and rendition of events” rather than the visualization of history. Apparently "representation" of the Holocaust had encountered limits. For example, in insightful films like Alain Resnais's "Night and Fog"(1955), Claude Lanzmann's "Shoah" (1985) and Stephen Spielberg's "Schindler's List" (1993) the immensity of the Holocaust's horror eluded filmmakers. Yet, documents on the Third Reich were in abundance and made available to historians immediately after 1945. Only the “revisionists” who denied that the Holocaust had taken place have rejected the overwhelming documentation of evidence. And they will surely not be convinced by more “documentary precision.”

To the contrary, the philosopher Juergen Habermas in his The New Conservatism argued for a historical visuality of “the images of that unloading ramp at Auschwitz” that represent for Germans a “traumatic refusal to pass away of a moral imperfect past tense that has been burned into our national history.” The unloading ramp at Auschwitz becomes a timeless, fixed image for Germans, “burned” in perpetuity into their “national history.” For Habermas, the Holocaust remains singular and cannot be compared to other crimes against humanity; and it remains exceptional and cannot be repeated historically. It stands representative in German history as a permanent negative image and as a unique event outside normalized history.

Habermas holds further that for Germans “life is linked to the life context in which Auschwitz was possible”...and...“our form of life is connected to that of our parents and grandparents...through a historical milieu that made us what and who we are today.” He concluded, Germans “cannot escape this milieu, because our identities, both as individuals and as Germans, are indissolubly interwoven with it....We stand by our traditions...if we do not want to disavow ourselves.”

On the one hand, the argument for a permanent image of Auschwitz burned into German national history, that is, a hypostatized image, one in stasis literally frozen, a permafrost of human events. On the other, the argument for a historical time continuum (“our form of life is connected ...through a historical milieu that made us what and who we are today”) to link the present to the past, weaving past, present and future in the here and now. But the link of the present to the past is a negative continuity, one that is to serve Germans today to reflect on their sinister historical inheritance.

Habermas's paradoxical reflections of historical stasis/continuity on the German past find concrete expression in his earlier political disclosure first published in the liberal weekly Die Zeit. There Habermas stated that "The only patriotism that does not estrange us from the West is a patriotism for the (German) constitution. One in conviction anchored union with the universal principles of the constitution could first spread after--and only through--Auschwitz. Whoever wants to drive out with a klischee like 'guilt-obsessed' the deep shame of that fact, whoever wants to call the Germans back to a conventional form of their national identity, destroys the only reliable basis that bind us to the West."

Universally Auschwitz stands for the destruction of Jews in Europe and for many as the end of Western values. Habermas holds that this negative symbol can have a redemptive dimension: The universal principles in the West German constitution that anchored West Germany to the political ideas of the West emerged as a consequence.

By locating Auschwitz as the genesis of German democracy Habermas proposes a new historical identity for West Germans. He resists the narrative of a normal German history; for him the events of the Nazi period of 1933 to 1945 have made that impossible. Yet while he rejects the “normal continuity” of German events, Habermas’s argument does rely on a “negative continuity” of the past: the “life context of Auschwitz” to the present.

From the "unloading ramp of Auschwitz," Habermas draws a "use value" of Germany's destructive past to forward democracy and the principles of the West. According to him Auschwitz stands for Germans as a permanent in their history--an "exceptionality", yet one coupled to their contemporary political education of Western values and reflection of German history, that is to their "learning" from their past.

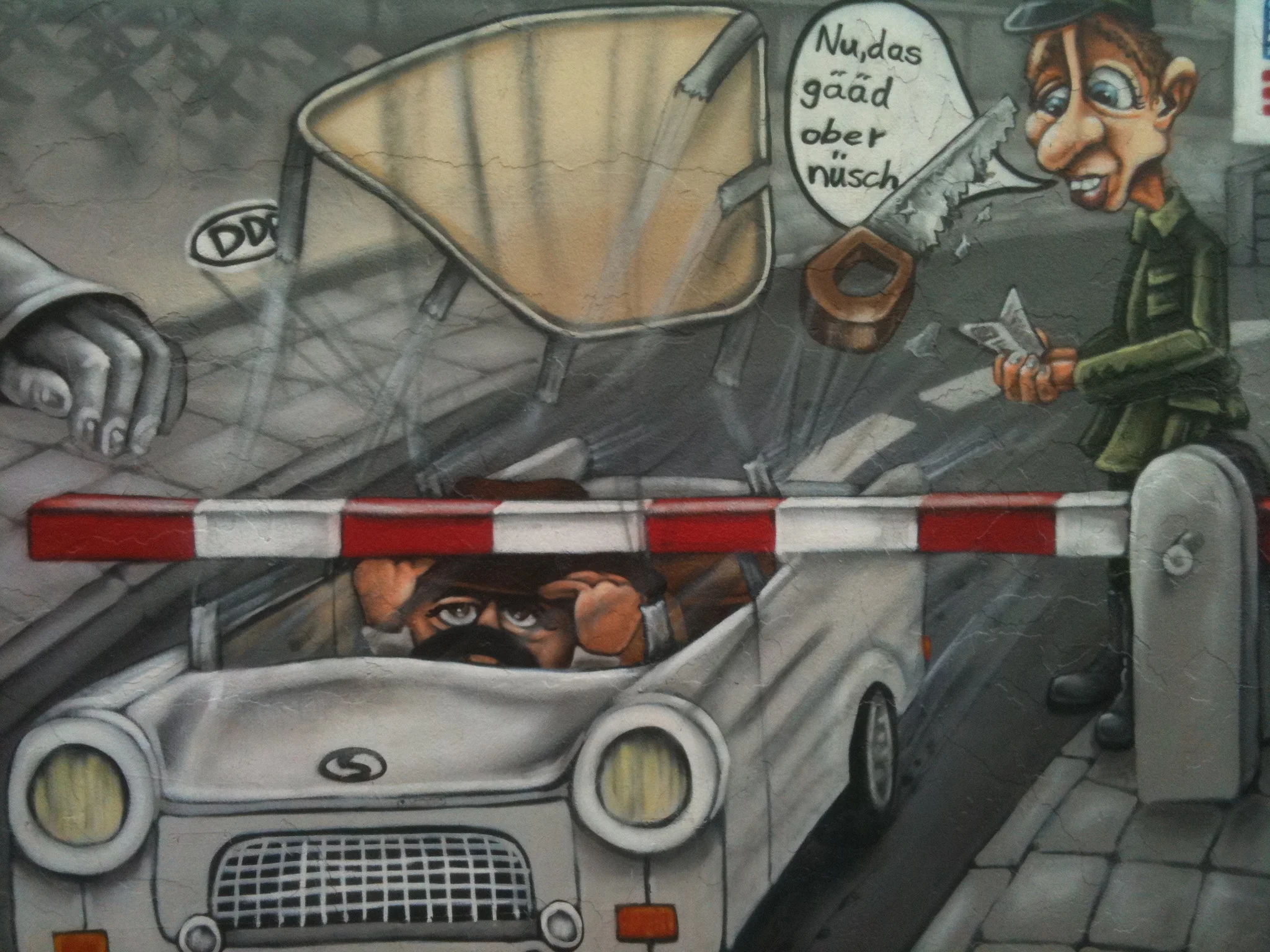

Although Habermas directed his writing to a West German public during the historian debates, since then East Germans have joined the West German nation and pledged to its constitution and traditions (1990). Yet, East German cultural pedagogy was different with another “history” of “German history” written. The East German ideologues defined fascism as a degenerate form of late bourgeois capitalism. And since capitalism was in West Germany, the argument went, so was fascism. That logic justified the East German’s building of a “barrier,’ known in the West as the Berlin Wall, but called by the communists the “antifascist protective rampart.” For the East German state the purpose of the “barrier” (and not Wall) was to shield the proletariat from the remnants of Nazism existing in capitalist West Germany. In the West theories of totalitarianism had compared communism to fascism and identified the East German state as a continuation of Hitler’s authoritarian government. Given the political culture of both German states, the fascists (or Nazis) where on the other side of the Berlin “barrier/wall.” With the "Berlin Republic" in place after unification, Habermas's historicizaton of the "German past" will require rethinking to address 16 million East Germans "in our national history" that was not their “own.”

As right as Habermas's arguments are in criticizing the neo-conservative historian's dubious normalization of the Nazi era, yet his insistence on integrating the "unloading ramp of Auschwitz" into the life of present and future Germans is founded on a historical determinism that is too reducing, too narrowing and too demanding. Similar to a Brechtian "learning play" (Lehrstueck) Habermas seeks to impose a cultural pedagogy that would visualize the past

("the unloading ramp of Auschwitz") to buttress a political program, the West German constitution and Western values, for contemporary Germans.

Yet, the Holocaust with the Auschwitz railway ramp stands too large and is too much a disturbing human problematic to serve speculative logic in cultural pedagogy or political agendas. The difficulty is that Auschwitz, the negative symbol of what went wrong in the 20th century, has a surplus of meanings. That surplus of meanings does not allow for historicist reductions with representing documents of the event and therefore cultural recuperation remains ambiguous.

The works of leading conservative and liberal historians outlined above reveal that their attempts to claim a "use value" of the destructive history of the Nazi era activated historical criticism in all directions. What their works also show is that the study of history is "open-ended" and that the past is not "past," rather it resists historicization and continues to work within a present-future, repelling homogenous narratives by constantly opening heterogeneous possibilities.

The unification of East and West Germany created a united German nation without the eastern provinces. Willy Brandt’s “Ostpolitik” was formalized in summer 1990 when the not yet united Germany signed a special treaty with Poland in Paris, recognizing its 1945 created eastern border. For many Germans today 1945 seems less like the end of history, rather the date 1989 has become the genesis of new historical narratives..."After the fall of the Wall...."

Remembrance of the victims of Hitler's destruction is found in books, films, photographs. Memorials have been constructed. In Berlin the Holocaust Memorial standing next to the Brandenburg Gate displays 3000 steles in remembrance of the dead. Not far away, the Jewish Museum documents the once culturally-rich presence, now absence, of Jews in Germany. After walking through several exhibits and sites like the "Garden of Exile and Emigration," the visitor arrives at the "dead end" of the "Holocaust Void." Entering in silence a group of several dozen visitors stand in a large, semi-dark, empty concrete chamber. After minutes of silence in the chamber, many visitors exist with tears streaming down their cheeks. Daniel Libeskind, the Museum's architect, sought to put into concrete space what Habermas put on paper: an effort to sensitize contemporaries into feeling/reflecting upon the brutality of the Holocaust. In designing the Museum, Libeskind had written "I thought to create a new Architecture for a time which would reflect an understanding of history."

After observing a visitor group of the "Holocaust Void" less than an hour later enjoying a rich German lunch with gusto and making plans for the evening's entertainment, I had my doubts of the effectiveness of Libeskind's cultural pedagogy. A Nietzschian thought came to mind that such "sensitivity" is usually a secondhand experience that can never become our own as it is too removed from our own lived world.

I shall never forget my uncle Miron, a survivor of Mauthausen-Gusen. His burden of the past was part of his existence. When I visited him in Binghamton, New York in the 1990s he quickly pulled me out of the driveway and frantically pushed me into the house. He shouted at me that I was in the line of fire of a Nazi machine gun nest on the wooded ridge behind his house! Yes, he had survived...sort of. Perhaps he had even saved my life.

It is difficult to place the history of "Contemporary Germany" under the normal academic genre of "national history" given the events of the last one hundred years. In the 20th century, the history of Germany was "made" and "remade" many times with each "national change" evoking a "new Germany." At least six major territorial transformations took place since 1871, three changes of "national capital," and about half a dozen contentious ideologies applied to governments from monarchy to democracy, fascism to occupation, communism to renewed democracy. The difficulty of "national history" was enhanced by each "new Germany" denouncing the politics of its predecessor. The task of the historian is, of course, to make sense of this human muddle, to offer a logic of events, a mode of comprehension, perhaps a cultural pedagogy. Yet, given the savagery of the previous and the ongoing butchery of humans in the 21st century, that task is monumental and at times historians and philosophers despair or perhaps feel "shame and anger over the explanations and interpretations--as sophisticated as they may be--by thinkers who claim to have found sense to this shit."

How to draw “history lessons” from our “history lesions?” Why is it so difficult for us to make “sense” of what we have made, our history? Already in 1740 Giambattista Vico had recognized that we as humans are always ahead in the making of things, but behind in understanding what we have made. Yet since history is a human “factum,” that is “what is made” by us, it is, Vico believed, knowable to us.

Several decades after Vico, the philosopher Immanuel Kant argued (in 1784) for enlightenment with his challenge of “dare to know” (sapere aude) and “truth will set you free.” The Enlightenment project that human reason is the tool for perfecting human life and human nature was severely damaged by the events of the 20th century, where reason as well became an instrument of destruction and violence of an unprecedented scale. Considering the events of the past one hundred years, we have many examples of how “knowledge is power” and less of how “knowledge is emancipation.” Perhaps we can change that history.

End notes

Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Entsorgung der deutschen Vergangenheit: Ein polemischer Essay zum "Historikerstreit" (Muenchen: C.H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1988), p.72, pp. 40-42, and pp. 100-101.

Ibid, p.168 for Wehler's argument that Germany was a carrier of the great Western traditions.

Ibid, p. 72.

Ibid, pp. 50-53.

M. Broszat/S. Friedlander, "A Controversy about the Historicization of National Socialism," New German Critique 44 (Spring/Summer 1988), p. 124.

Juergen Habermas, The New Conservatism: Cultural Criticism and the Historians' Debate, ed. and trans. Shierry Nicholson (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1989), pp. 229-230.

Ibid, p. 233.

J. Habermas, "Eine Art Schadensabwicklung. Apologetische Tendenzen in der deutschen Zeitgeschichtsschreibung," Die Zeit, 11 June 1986, pp. 120-136. See also Historische Zeitschrift 242, pp. 265-289.

For a critique of Habermas's model see Sande Cohen, "Habermas's Bureaucratization of the Final Solution," in his Academia and the Luster of Capital (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), pp. 63-80.

See Daniel Libeskind, "The Jewish Museum Berlin: Between the Lines," www. daniel-libeskind.com, where he states that three basic ideas "formed the foundation for the Jewish Museum's design" and one is" The necessity to integrate physically and spiritually the meaning of the Holocaust into the consciousness and memory of the city of Berlin."

See Friedrich Nietzsche's essay, The Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life.

J.-F. Lyotard, The Differend: Phrases in Dispute, trans. G. Van Den Abbeele (Minnesota: The University of Minnesota Press, 1988), p. 98.

Leon Pompa, editor and translator, Vico Selected Writings (Cambridge University Press,

Binghamton, 1982), see pp. 33-56 where Vico exposits his historical method.