Berlin: Twenty Years After the Fall of the Wall

Petermichael von Bawey

““Humans make their own history…under circumstances directly encountered, given, and transmitted from the past.”

- Karl Marx”

Walking with Urban Ghosts

In Berlin, flanerie sprouts historical roots. Strolling through the city stretches the mind as well as the body, and loco-motion takes on several dimensions. One street leads not only to another it takes the visitor through several epochs of Berlin’s history. From royal to imperial city, from republican to fascist capital, and from bombed rubble to capitalist and communist reconstruction, fragments, traces or renovations of historical Berlin jostle against contemporary buildings as styles rudely collide to give the city an urban jounce unlike any other.

Before bombs destroyed over half of Berlin and marred its historical profile, Alfred Doeblin’s novel Berlin Alexanderplatz, characterized the city with his protagonist Franz Bieberkopf, who lost his briefly enjoyed wealth and status, his girlfriend and his arm, only to bounce back, stroll care-free again on the Alexanderplatz to take pleasure in his urban life!

I feel that is how Berliners would like us to understand their city: No matter how hard the blows of existence fall, Berliners will rebound and spring back into the midst of human activity to enjoy life in their city.

At least that is what I thought as I walked through the center of Berlin twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and sensed the energy of a vibrant and open city.

Thousands lined-up in front of the Reichstag, now the National Parliament, to enter the glass dome, permitting visitors to see German government in action. Pedestrians strolled leisurely through the Brandenburg Tor (Gate), the city’s symbol, walking from one side to the other, and enjoying the shops along Unter den Linden to the east, or the wooded Tiergarten to the west.

Next to the Tiergarten the busy Potsdamer Platz with shoppers rushing from one arcade to another, or couples searching for a restaurant, a film, or merely taking in the many attractions of this once again popular square. Others clustered around the odd shapes of the numerous charcoal, concrete blocks, exploring the Holocaust Memorial near-by.

Twenty years ago, there was no Memorial and the Potsdamer Platz was one of Berlin’s largest vacant lots with the Wall to the east, a few ruins to the west, and only rabbits running freely.

Wim Wender’s film Himmel ueber Berlin (Wings of Desire) offers poignant images of that forlorn empty lot with an old man, apparently a retired historian, sitting alone on an abandoned, ratty sofa and musing about the stories he has to tell of old Berlin and the Potsdamer Platz, once Berlin’s busiest intersection with the first traffic light for car traffic, luxurious hotels, magnificent apartment blocks—all gone, remaining only an empty lot and a forsaken storyteller without an audience.

The Reichstag, now assiduously restored by the architect Norman Forster, was then an infrequently visited German history museum; and the Brandenburg Tor was inaccessible and sealed off by the Wall on its western side, blocked by the Vopos, the People’s Police, in the east. To the east of Brandenburg Tor, Berlin’s famous Pariser Platz where the embassies of Great Britain, France and the United States once stood majestically was in ruins. Only the Soviet Embassy in Stalinist architectural style (the wedding cake form) of post-war Eastern Europe—as in Moscow, Bucharest or Warsaw—dominated the once grand boulevard Unter den Linden. Dreary, oppressive concrete blocks of power, lacking in balance and form, in aesthetics and urban dimension dominated East Berlin.

Walking from the Brandenburg Tor eastward to the city’s historic center stands the neo-classical edifice of the Humboldt University, after the brothers Wilhelm, eminent humanist, and Alexander, world-known naturalist, who advanced the free spirit of modern education. Yet the foyer of the University displays Karl Marx’s bust and his theses on Feuerbach engraved in marble to emphasize the definitive communist response to the Humboldt spirit. To this day their conflicting philosophies remain part of the Humboldt University, however, the words of the brothers have the greater say.

The neo-classical Neue Wache (Guard House) is re-united Germany’s first “National Memorial” conceived by the new Germany’s former Chancellor Helmut Kohl, the political engineer of the re-unification. Originally designed by Friedrich Schinkel in martial architectural forms, the Guard House stands today with Kaithe Kollwitz’s Pieta sculpture in the center, a symbol pleading for peace.

The Arsenal, the former “Armory” of the Imperial Palace, flanks the Neue Wache. It is the city’s oldest, baroque building, and now the new “Museum of German History.” In the seventies, the building was dedicated to V.I. Lenin housing a collection of memorabilia in portrayal of his political work.

Across the boulevard, the neo-classic Opera dominates, dating to the rule of Fredrick the Great (1740-1780); next to it, Opera Square, earlier with a socialist label of “Bebelplatz “ after August Bebel who had advocated rights of workers and women in late 19th century Berlin; adjacent the baroque palace with the plaque “Lenin worked in this building.”

Now that history is gone. Today the square carries its original name and the baroque palace is home to the University’s Law Faculty.

In Berlin, one level of German history has frequently replaced another as the city constantly reinvented its historical identity.

Continuing southward across the Spree River on Schinkel’s bridge with statues of the life and death of a Greek warrior (recently remounted), the visitor arrives at “Museum Island” on the east, and an empty lot to the west. In front, the Berlin Dom stands grandly; and to the left the Island’s five museums—the Oriental Museum with the bust of Nefertiti, the Pergamum Museum with its Hellenistic temple and Babylonian Gate, and Schinkel’s Alte Nationalgalerie in front, its Doric columns casting the visitor into the ancient, classical world.

“Athens on the Spree” was the name given to Berlin in a by-gone age.

Some may remember that on the vacant lot across Museum Island stood the “Palace of the Republic,” containing East Germany’s “Volkskammer” (People’s Chamber) and the public “Kulturhaus,” or “House of Culture.” Many East German youth used to meet here for ice cream or coffee and rock and roll to the sound of the Puddies.

The “Palace of the Republic” was East Germany’s version of “Socialism on the Spree” and stood in stark contrast to the neo-classicism of historical Berlin in a vain attempt to replace “Athens on the Spree.”

The new German government ordered the asbestos infected “Palace” torn down, despite numerous protests by East Berliners. In progress now is the reconstruction of the façade of the historic Imperial Palace that once faced Museum Island, but was demolished by the East German government to “efface relics of feudalism.”

Few may recall that the Arsensal not only housed artifacts of Lenin’s life but the East German Honor Guard—the “Friedrich-Engels-Ehrengarde,” and the Neue Wache stood as a memorial to the ‘victims of fascism.” Each Wednesday afternoon the Friedrich Engel’s Guard goose-stepped (sic) from the Arsenal to the Wache thrilling crowds of Western Allies--American, British and French soldiers applauding the spectacle of “Old Prussian” military tradition, communist style.

During socialist East Berlin, Museum Island was mostly in ruins, Nefertiti located in the stables of Charlottenburg Palace in the west, and trees grew out of the ruins of the Berlin Dom. Historical Berlin was left to deterioration and decay, parts appropriated and used in a paradoxical manner as the Neue Wache to mark the era of “real, existing socialism.”

For planners of “real, existing socialism,” the old Berlin of feudal or bourgeois origin had to give way to architecture for the people. Urban spaces for the working masses were to replace earlier sites conceived for the individual, the Renaissance notion of urban planning founded in the writings of Alberti.

This socialist thinking found fulfillment in the constructions of the super-sized and empty Alexander Platz, the asparagus-ugly and tall Television Tower, or the vast pre-fabricated monotone cement cages or apartment complexes in the East Berlin districts Friedrichsfelde and Marzahn, forlorn and densely cemented blocks and homes to urban alienation.

Only with celebration of the 750 years anniversary of Berlin in 1987, did East Germany permit western financing to save and restore parts of historical Berlin such as the Berlin Dom, the German and French Dom on the Gendarmen Markt, the old French quarter, and the Nikolaus Viertel, the oldest district of the city.

Conversing with Urban Spirits

A “counter-culture” emerged in East Berlin, particularly in Prenzlauer Berg, considered by many today the smartest district of Berlin, where the affluent enjoy the renovated historicist style of nineteenth century apartment blocks, spacious lofts, open markets, and chic bars and restaurants.

Under the GDR, Prenzlauer Berg was a derelict district, a left-over from 19th century bourgeois Berlin with houses crumbling, apartments vacant, lacking in plumbing and central heating, neighborhood stores shabby. Yet this deliberate government neglect of historic Berlin made the district a perfect venue for artists to settle-in and attempt to produce a cultural alternative to the hegemonic mainstream fare.

Artistic debates on the modern and post-modern, poetry readings, East German rock music with Fabrik and Zwitschermaschine dominated the cultural scene, and Sascha Anderson—lyricist, musician, and essayist—was the recognized, dominant artist of Prenzlauer Berg’s counter-culture. That is, until the fall of the Wall. Then Anderson stood exposed as agent of the state security services, the notorious Stasi.

He was an official informer reporting regularly on “enemies of the state,” who were his artist friends and colleagues. In East Berlin, the Stasi dominated and was omnipresent everywhere even in the alternative culture of Prenzlauer Berg, and any aesthetic of resistance as Sascha Anderson vividly illustrated was transformed into an aesthetic of betrayal.

Popular East German rock groups like the Puddies were under Stasi tutelage—their lyrics censored—and their performances monitored.

Much of this is forgotten today as East Berliners avidly invent their counter-culture.

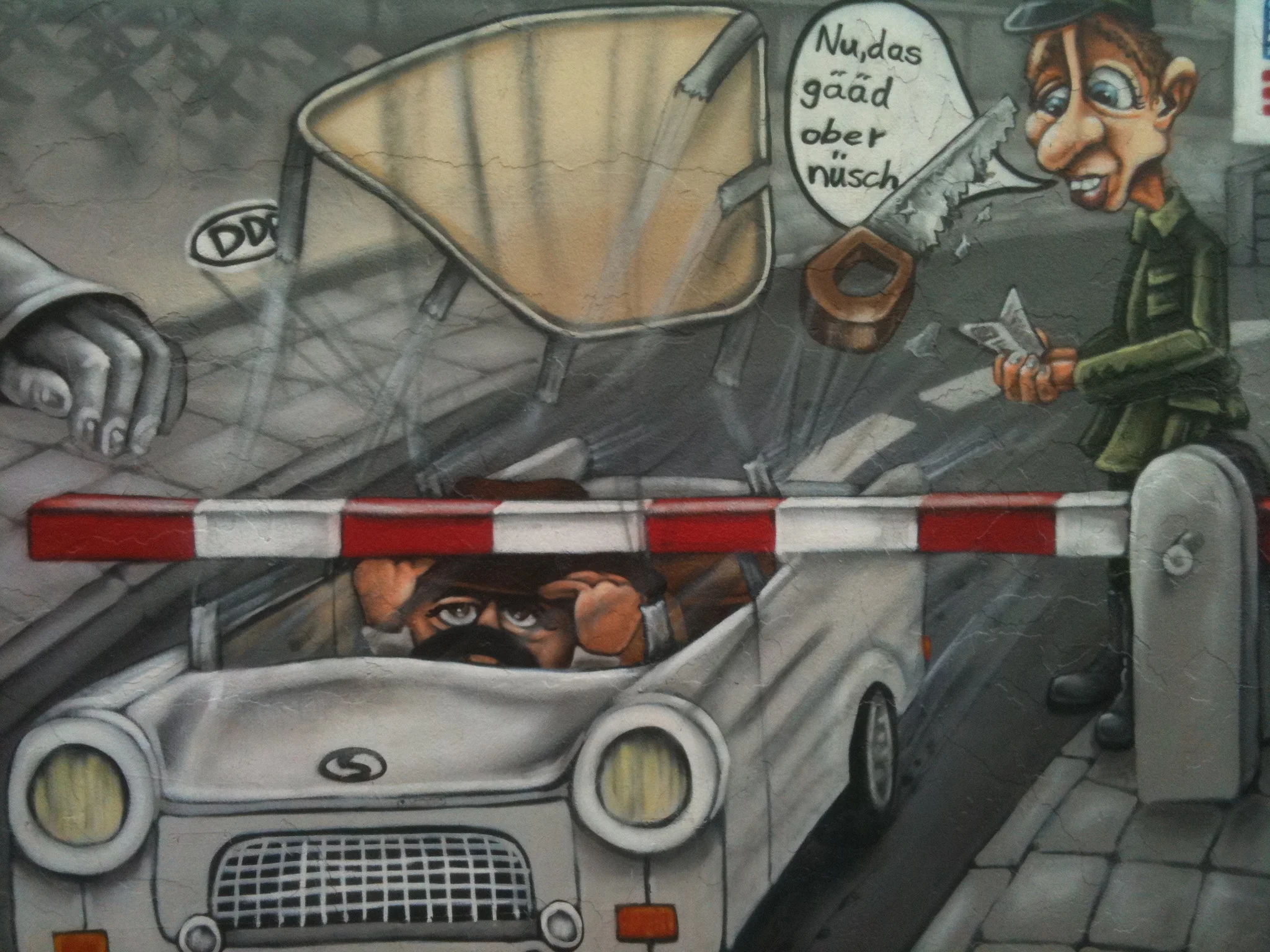

For the twentieth anniversary celebrations of the fall of the Wall, the “Wall Art” of the East Side Gallery underwent renovation. Tourists flocked to the Gallery to admire the Wall paintings. Yet today few know that there was no “Wall Art” here when the Wall stood (1961-1989).

East Berliners, having faced a blank, whitewashed and “civilized” Wall for twenty-eight years, expressed a desire for “Wall Art” six months after the Wall’s fall. Yet the “Wall Art” the world witnessed when the Wall stood was an art of resistance on the other side in West Berlin. It was also a tourist attraction, known as the “eight wonder of the world” attracting more than six million visitors annually.

Nevertheless, between May and October 1990 more than one hundred artists from around the world participated in painting over one kilometer of pristine Wall surface, and the “East Side Gallery” was born.

Normally the Wall in East Berlin consisted of inferior cement segments typical of the hinterland construction, but this site, where official visitors of state traveled from the airport to the city center, was constructed with the same superior “Wall 75 segments” that were used for the frontier Wall facing West Berlin. As a result, a smooth Wall surface allowed artists to paint the Wall during the transition period when West Germany absorbed East Germany.

Thierry Noir participated and painted about thirty meters of the same comical series that had made him famous in the West.

In 1992, the municipality of Berlin moved the East Side Gallery to a neighboring site and made it a permanent exhibit of the city.

Many of the East Side Gallery’s “Wall Paintings” are artistic, clever, even funny, yet they can only remain paintings on an urban wall, not Wall Art. The dynamic of Wall Art is lacking, so the protest, and the reason for that protest, the Wall, is gone. What was gone as well was the spirit of protest that had created Wall Art in West Berlin.

The most known painters of the Wall were two French artists who had settled in West Berlin: Christopher Bouchet and Thierry Noire. When asked why he painted the Wall, Bouchet replied, “To have a little bit of a revolt.”

He and Noir had lived in Kreuzberg—known as SO36—only five meters from the Wall in 1984. Their revolt was a creative response to the violence the Wall inflicted on the city and its inhabitants.

They realized they could not “beautify” the Wall. Noir wrote, “We are not trying to make the Wall beautiful, because that, in fact, is absolutely impossible. Eighty persons were killed trying to jump over the Berlin Wall, to escape to West Berlin, so you can never cover that Wall with hundreds of kilos of color, it will stay the same. One bloody monster, one old crocodile, that from time to time wakes, eats somebody up, and falls back to sleep until the next time.” 40

With that realistic view Noir attempted to bring “pleasure” to those living next to the “crocodile” and to express as well a “political act” of protest: To counter the terror of the Wall with the play of colors and forms, the naiveté and joy of what was called “Wall Power,” a West Berlin version of “Flower Power.”

The GDR erected the Wall to built “real, existing socialism,” transform its capital into “socialist Berlin” and isolate West Berlin. Attempts to express cultural alternatives to the hegemonic ideology were suffocated or infiltrated and rendered ineffective. The rare publication in 1972 of Plenzdorf’s novel The Suffering of Young W., where a young apprentice searches for individuality—like Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye—was an anomaly since conformity and not individuality was the paradigm for youth in East Berlin.

In turn, the youth of West Berlin responded to the Wall with a dynamic culture that not only challenged the “real, existing socialism” of the east but the capitalism of the west as well.

Revisiting Wall Culture SO36

““You won’t get us out of here. This is our house!

Ton, Steine, Scherben””

“SO36” was the official designation of the southeastern district of Kreuzberg in West Berlin, surrounded on three sides by the Berlin Wall. Given that dismal location, the area did not have much of a future. As late as 1970 Kreuzberg apartment blocks still damaged from the bombing raids of WWII, most of its inhabitants long gone, stood vacant. Some retired Berliners defiantly remained while students and Turkish immigrants flocked to the area in search of cheap rent and available space. Many buildings, nevertheless, stood empty awaiting the municipal government’s directive for demolition to construct a new urban center—a capitalist cement version of East German reconstruction. That never happened.

In summer of 1971 over three hundred students, apprentices and social workers occupied a factory complex at Mariannen Platz, one of Kreuzberg’s central squares. Apprentices had already rented the second floor of the complex and now took charge of the other two floors to found the “Jugendcentrum Kreuzberg” (“Youth Center Kreuzberg”).

The “Youth Center” renovated the three floors and opened workspaces for apprentices, rooms for a theater group, and offices for youth councilors. Negotiations with the municipal government led to the signing of a rental contract and discussions of occupying the “Martha-Maria Haus” an adjacent building to the factory complex and part of the former Bethanien Hospital Complex at Mariannen Square, which, destined for demolition, had stood vacant for some time.

Then West Berlin erupted with massive protests and violent clashes between police and students. On 4 December 1971, undercover police fatally shot Georg von Rauch, a self-styled anarchist and urban guerilla who had escaped police custody in February of that year.

West Berlin had seen nothing like it since 2 June 1967 when the visit of the Shah of Iran led to demonstrations, violence, and a police officer’s fatal wounding of Benno Ohnesorge, a student who had taken part in his first demonstration.

Four days after the killing of Georg von Rauch by the police, a large “teach-in” took place at the Technical University, where students, sympathetic professors, journalists and intellectuals debated the events. The new West German rock group “Ton, Steine, Scherben” (“Sound, Stones, Glass Shards”) participated and played from their album “Keine Macht fuer Niemand”—“No Power to Anyone”—with songs like “Mach kaputt was dich kaputt macht”—“Destroy what destroys you.”

The mood was combative. On one side, the protestors outraged that another “police murder” had taken place in their city. On the other, the average West Berliner—often influenced by the conservative Axel Springer press with its anti-leftist broadsheet “BZ”—and the West Berlin police, unlike other police at that time trained in military combat and often mistaking leftist students for communists, who should live on the other side of the Wall.

The squatters in the factory complex at the Mariannen Square used these political events to occupy the empty adjacent “Martha-Maria Haus.” Evading police, penetrating fences and barbed wire, the occupiers barricaded in, called on the student protestors to support them, and baptized their newly conquered squat the “Georg von Rauch Haus’ on 8 December 1971. 23

Students responded with large demonstrations on the Mariannnen Square supporting the squatters; and Ton, Steine, Scherben sang their new composition the “Rauch Haus Song”—with “Ihr krieg uns hier nicht raus! Das ist unser Haus!” (“You won’t get us out of here! This is our house!”). 24

Given the volatile and tense mood of youth in West Berlin in the winter of 1971-72, the municipal government acquiesced to the occupation and signed a contract with the squatters, permitting the “Georg von Rauch Haus” to become a cultural center and inexpensive home for aspiring artists. It still fulfills that mission today.

Next to the Rauch Haus stands the Benthanien Hospital, which too was occupied and serves to this day as “Kuenstlerhaus” or “Artist Residence” and currently has offices for the German Academic Exchange (DAAD). 25

Just a few blocks from Mariannen Square, stands the “Ausbildungswerk Kreuzberg” (“Rehabilitation and Vocational Training Center Kreuzberg”) founded in 1978. Started by artisans and social workers, the Ausbildungswerk presented West Berlin’s municipal government with a fascinating project: The Ausbildungswerk would rehabilitate teenage “street kids”—drug users, prostitutes, homeless, jobless or uneducated youth—and train them as apprentices in trades as carpenter, plumber, electrician, painter, or bricklayer to engage them in the renovation of empty and historic apartment buildings in the neighborhood. The apartment buildings were from the Gruenderzeit or “Foundation Period” the Berlin of the 1870s and constructed in the “historicist style” of that age. The Senate of West Berlin approved the project and the Ausbildungswerk recruited “street kids” who lived together in one apartment building, taking turns in cooking, cleaning, and repairing their residence, while learning a trade and renovating apartment buildings nearby.

A decade later, the Ausbildungswerk opened the restaurant “Mundtwerk” on its ground floor under the direction of a French chef (a former French army sergeant) and trained apprentices to prepare and serve la cuisine francaise. The Ausbildungswerk still serves Berliners excellent food today. 26

Kreuzberg SO36, entrapped on three sides by the Berlin Wall, once a forlorn and bomb-ruined neighborhood destined for demolition and cement block “renewal/devastation” stands saved from the hammer by its young residence, who at times fought police and the municipal authority, to establish their own cultural scene, gentrify the neighborhood and offer lost youth a new lease on life. Today government officials, artists, yuppie entrepreneurs and Turkish immigrants live in the neighborhood side-by-side, many attracted by its elegant historic buildings, yet unaware of the district’s counter-culture and its former battles to save one of Berlin’s historic neighborhoods.

Youth culture in Kreuzberg SO36 became a model exported to other areas of West Berlin.

In 1976, the group “Factory for Culture, Sport and Artisan Work” (“Fabrik fuer Kultur, Sport und Handwerk”), originally in Kreuzberg, occupied two factory floors in Schoeneberg, a middle class neighborhood to the southwest of the city. The space opened for sport activities, political discussions and a food coop, West Berlin’s first.

Two years later the Fabrik presented a circus show at the Kuenstlerhaus Bethanien, which served as model for its future activities: A mélange of clown and animal acts, cabaret and juggling, discussion and advice on the environment and new technology, healthy eating and vegetarian diet, new models for education and artisan training.

On 9 June 1979, the Fabrik occupied the former UfA (Universal) Film studios in West Berlin Tempelhof, a vast terrain with a complex of buildings standing vacant and awaiting the demolition order of the municipal government. Instead, the Berlin Senate permitted the occupants to develop the site with their cultural activities.

Taking the name “ufaFabrik” a group of forty-five people engaged themselves to live and work together, receive equal pay and develop projects in common. This was a universal hippie model—shown in Dennis Hopper’s film Easy Rider—and shared by bio-food farmers in Humboldt County, California, for example, or by those in the Ausbildungswerk Kreuzberg.

The large hall of the UfA studio was renovated and transformed for circus and theater performances, a movie theater was opened, and the terrain was modified to house a biological bakery and food store, an animal menagerie for visiting children was established and solar panels and windmills were installed, giving creditability to alternative modes of living, eating, and energy.

Today the ufaFabrik is one of Berlin’s largest cultural centers with restaurants and cafes, bio-stores and alternative energy—the largest solar panel installation in the city—a Brazilian samba band, a circus and circus school for children, in-door and out-door movie theaters, a cabaret and theater group, an animal farm and a playground for children. 27

Juppy, creative spirit of the ufaFabrik, described it as a “biotope of culture” and a direct reaction to the Berlin Wall: “We in West Berlin always had to consider what we can do so that the injustice of the Wall does not constantly weigh-down our existence so that we don’t run around daily in a lousy mood.” 28 Juppy’s response was the ufaFabrik.

Walter Momper, former major of West Berlin, expressed the mood of Berlin’s Wall Years with these words: “We have no regrets for the Wall, but we will miss Wall Art!”

I would add: And West Berlin’s counter-culture!

End Notes

40 Thierry Noir, “The Story of the Berlin Wall,” photocopy handout given to the author by Noir in 1997.

23 See www. Georg von Rauch Haus. de

24 Ibid.

25 See www. Kuenstlerhaus.de.

26 See www.Ausbildungswerk Kreuzberg.de.

27 See www.ufaFabrik Berlin.de.

28 Olaf Leitner, ed.,West-Berlin! Westberlin! Berlin (West)! Verlag Schwarzkopf&Schwarzkopf: Berlin, 2002) 293.